Simplifying build in C++ (part 1)

on Build systems, C++

What is the first thing you do when you start a new project? Me, I install Google Test (or an equivalent) to make sure I have a decent test coverage from the start.

What then? Boost (which module)? range-v3? sqlpp11? curl? openssl? Those are just very general dependencies I’ve seen in a lot of projects. There’s no way around it, the standard library cannot cover everything, so a project will need a 3rd party library to run unit tests, access the web, decode files, handle cryptography or store data. And I’m not even touching the UI/rendering aspect.

Most languages have solved that problem with a package manager that comes with the language. Python has pip, JS has npm, Rust has cargo, Ruby has gem. Heck, even Perl has had cpan for decades. What does C++ have? A couple of projects, some with interesting promises, but still nothing comparable.

This is a serious issue. Lack of productivity in C++ is one of the most common arguments I hear against C++, and the efforts needed to use 3rd party software (or even another library you wrote, really) is, in my opinion, one of the main reasons why.

The plot thickens

Isabella Muerte did a great job at CppCon this year to explain what I just did in a much more metal way (will link the talk when it’s published). Following a few discussions with her, I concluded that package management is only one of the problems.

Let’s say you have a package manager that lets you install whatever 3rd party library on your system. How do you tell your build system to use it? Ideally you would like to just use the Modules TS and do import. Except you can’t, because your build system has no way to know which modules your code requires unless you tell it… again. Isabella made a great post about that issue.

But let’s imagine for a second that the Module TS gets fixed and the build system can query your code to get the list of dependencies you require. That’s great, you followed the DRY principle. But still, your build system doesn’t know how to install a missing dependency (or even where to find it if installed). Your package manager is supposed to handle that. So again, you violate DRY by putting the list of dependencies you require twice: once in the build files and once in the package manager.

And then, what happens when you want to publish your library as a package? You have to tell the package manager what kind of flags to propagate to users (include dirs, defines, lib flags…). If you want to avoid breaking DRY again, you use pkg-config and provide a .pc that’s generated from your build files and that your package manager can use. Except very few libraries do that. I’ve looked at a good sample of Conan package scripts and almost all of them describe the build interface of the package again because it has no way to extract it from the build system.

False promises

Some developers looked at this problem and concluded that the solution was to merge both package manager and build system. After all, other languages have done it and it works! Alas, it’s too late.

C++ has been around for some time and no solution has taken over. CMake is probably the most common, but it’s far from the only one. So creating a new package + build tool wouldn’t solve anything today. Even if it was the best of the world, it would require every project to rewrite its build files. This would take time. Transitition would take years and until a significant portion of them has been migrated, the situation would not improve for day to day C++ dev.

I’m not saying we’re doomed to write CMakeLists.txt for the rest of our lives, but any serious solution would have to offer some degree of compatibility with existing code so that we could get results quick. If you put rewriting the full build of Boost (or any similar popular library) to a new and almost unused (yet) build system on the critical path, you’re not going to make any progress.

A potential solution

To recap, a package management solution should offer the following:

- Follow DRY. No duplication of information should occur between the build system and the package manager.

- Compatibility with existing build systems. It should be able to integrate with CMake, Boost.Build, Meson, …

- Ensure packages are compatible with each other and follow whatever build profile (compiler, standard, target machine…) was defined by the user at top level.

- Prefer config files to scripting. If scripting must be done, do not write a new language, and seriously consider using C++. Developers (especially newbies) should not be asked to learn another programming language to be able to do C++.

Common build interface

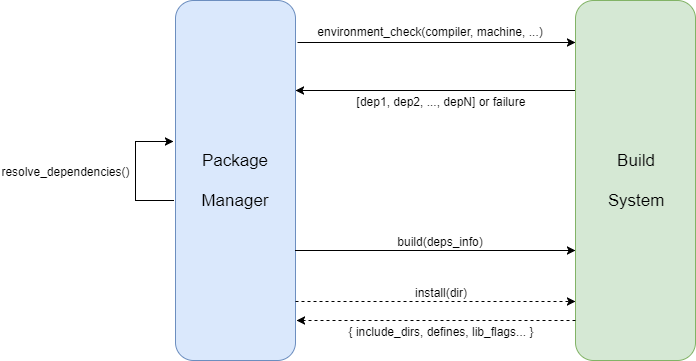

To me, the best (and maybe only) way to solve DRY (and some other issues) would be to design and implement a common build interface that package managers could use to integrate with build systems. Here’s a schematic overview of how it could work, using the package manager as the top level orchestrator of any build:

- Environment check

The package manager gives the build system all the information about the environment: which compiler to use, which standard and ABI flags are in use, the build type (debug/release) and the target architecture. The build system is expected to check if it can work with that. It should not try to work around the build flags to raise the standard version or anything else to satisfy a build requirement from the project. Either it can work with it, or it fails the environment check. - Dependency listing

Once the environment check is passed, the build system should return the list of dependencies required (with the acceptable versions) for that build. How it obtains that list is its responsibility and the package manager should not interfere. Today it could be written in the build files but tomorrow it could be queried from source with some kind of/showImportstoggle to the compiler. Each dependency should be explicitely declared as public or private. - Dependency resolution

The package manager can then query its storage (local or remote) to check if all the required dependencies are available for the current environment settings. If some packages are missing, it could either build them (by recursively running this whole procedure) or fail depending on user input. Of course, if no recipe is available (or if a version conflict is detected), it should fail too. - Build

Once all dependencies are installed, the package manager should call the build system again to build the module. It should provide the build interface of each dependency (collection of include/link/define flags). - Install

If the built module is supposed to be installed (either because it’s being built as a dependency for another one or because the user explicitely asked for it), the build system should install it at a location provided by the package manager. It should also provide the build interface of the module to the package manager so that it can be reused by another.

This procedure robs the existing build systems of some of their roles today. Some of them like to try to find or even install dependencies, others try to set/overwrite build flags to satisfy some requirements. For a proper separation of concerns, that should be disabled when working with a package manager to ensure a consistent build across packages.

I believe those changes could remain tactical and not force maintainers to rewrite their build files completely to be compatible. They could even be proposed by packagers in pull requests. And until build systems are patched to work with that interface, it should still possible to duplicate information between packager managers and build files as a transitory solution, in a way similar to what Conan packages look like today.

That way, we could quickly offer package management of existing popular libraries today while preparing for the future. That interface could also be implemented by any future build system so that it can integrate with older libraries without being tied to an older system.

(Partial) conclusion

So far, we’ve seen a potential solution to address the first three issues: uphold DRY, offer compatibility with existing libraries and ensure the results are ABI compatible by taking control of the build flags.

One last item remains (and possibly the most controversial): not using a language other than C++ to describe how to a package a C++ project. Since most of the custom scripting would be removed by using a common build interface, I think that question is best left unanswered for now. But don’t despair, it will come back in the next post when we discuss how to improve the build systems themselves. Stay tuned!

PS: Of course this is just an idea, maybe an embryo of a proposal. Feel free to send any comment, objection, suggestion or encouragement by email, Twitter or on CppChat.

Edit: I wrote a quick follow-up to clarify some points after reading the reactions.