PhysFS performance, a story of threading and locking

on C++, Game development

Loading screens are pretty cool. They let artists showcase some nice art while the intro theme song starts playing. Used well, they can set up the stage for the eventual play by putting the player in the mood. But that’s only a side effect. Their main purpose is to keep the user busy while your game loads and initialize everything it needs to render the main menu, and possibly more. But after the first hundred or so starts, the experience may get old. Especially if that loading bar seems to be stuck forever.

Our Grand Strategy titles at Paradox have a reputation to not be on the fast side to load up, especially considering that they are not exactly next-gen graphics games with tens of gigabytes of assets. A couple months back, I decided to take a look at how Clausewitz (our internal engine) loads up stuff and what took so long.

The answer was interesting: most of the time was spent doing nothing. More precisely, either doing nothing by sleeping on a condition, or burning CPU cycles waiting a boolean to become true. We had a locking problem.

Thread safe, but not thread efficient

The big lock contention was on file access. Every read, write, open, close or enumerate ended up locking a mutex or spin lock somewhere. And most of it was not even due to our engine.

To ease up filesystem access, we rely on a 3rd party library called PhysicsFS, or PhysFS. It’s a pretty handy way of mounting several directories and archives under the same logical hierarchy and treat it as one, handling things like priority when resolving names which is crucial to support DLCs and user mods properly. It also supports a variety of platforms and archive formats. But it had one fatal flaw: it’s bad at threading. Really bad.

Some time ago, my predecessors decided to load up the game data from disk with several concurrent threads. While it was probably efficient at the time, today it had become quite the pain, since PhysFS implements thread safety through one global mutex that is locked on all API calls. Meaning one thread doing a read() would block any other trying to either read, open, close or seek a file (be it the same or another one).

static void *stateLock = NULL; /* protects other PhysFS static state. */

int PHYSFS_close(PHYSFS_File *_handle)

{

FileHandle *handle = (FileHandle *) _handle;

int rc;

__PHYSFS_platformGrabMutex(stateLock);

PhysFS has been there for quite sometime, and at some point an issue was raised about the thread safety of the API, which was resolved by putting a global mutex or two. While probably good enough at the time, it turns out to be a serious performance killer on a modern machine with 8 cores trying to access the filesystem concurrently. In several cases it turned out to be even slower than processing the same data serially in one thread.

Improving the threading model

Luckily for me, it had been recently decided that we would embed a modified copy of PhysFS in our engine, which made it easier to tinker with it until I had something satisfactory. While I could probably make those changes public, they would have little chance of being accepted mainstream as is, as one of my first decision was to drop usage of C in favour of C++. Instead, I’ll describe here was I did to make our implementation more friendly to threads.

As I hinted, the first thing I did was to tweak the build (of course!) to have our local fork of PhysFS compiled by a C++ instead of a C compiler. Our engine is entirely built in C++ and there was little reason for me to keep dealing with C in 2020, especially if locks were involved. For example using macros and gotos instead of RAII to ensure proper unlocking on early returns is pure masochism if you ask me. See for yourself:

#define GOTO(e, g) do { if (e) PHYSFS_setErrorCode(e); goto g; } while (0)

#define GOTO_ERRPASS(g) do { goto g; } while (0)

#define GOTO_IF(c, e, g) do { if (c) { if (e) PHYSFS_setErrorCode(e); goto g; } } while (0)

#define GOTO_IF_ERRPASS(c, g) do { if (c) { goto g; } } while (0)

#define GOTO_MUTEX(e, m, g) do { if (e) PHYSFS_setErrorCode(e); __PHYSFS_platformReleaseMutex(m); goto g; } while (0)

#define GOTO_MUTEX_ERRPASS(m, g) do { __PHYSFS_platformReleaseMutex(m); goto g; } while (0)

#define GOTO_IF_MUTEX(c, e, m, g) do { if (c) { if (e) PHYSFS_setErrorCode(e); __PHYSFS_platformReleaseMutex(m); goto g; } } while (0)

#define GOTO_IF_MUTEX_ERRPASS(c, m, g) do { if (c) { __PHYSFS_platformReleaseMutex(m); goto g; } } while (0)

Once that was done, I was able to put all the API state (a few globals) inside a struct that would only be accessed through a RAII accessor that would lock/unlock on construction and destruction. Then I started checking if that state could be split into several sub-structures with each their locks. This allowed me to have a clearer understanding of the data model and where the contention was.

As it turned out, about 75% of the locking was done to ensure that the filesystem configuration was not changed during pathname resolution. As PhysFS aggregates several mount points under one root (like UNIX mount does), the API needed to lock the list of mount points to protect against data races should another thread mount or unmount a path at the same time.

The thing is, mounting or unmounting paths is a rare and specific operation. It is usually set up once when the game starts, and only change at very specific places (for example if the game allows to enable/disable mods on the fly). Almost 100% of the calls to mount() and unmount() are done while no other thread is loading as even with locks it would make the result unpredictable. Locking the whole API for that very rare case made no sense for us.

To solve this I introduced a freeze_config() call in the PhysFS API that would turn the configuration read-only internally. With proper use of const accessors, it allowed me to bypass locking entirely for read accesses to configuration while the freeze flag was set. Any non-const access to the configuration state in that mode would assert or throw an exception to trap the logic error. Since all access to the configuration singleton was now handled by a RAII accessor, it was easy to handle the change at one single point and have the whole PhysFS code behave like I wanted. This reduced the lock contention on FS access drastically, making threaded code actually run in parallel.

The next lock I got rid off was the error lock. PhysFS keeps track of errors by having a form of errno per thread which is stored inside a linked list of thread id / error code pairs:

typedef struct __PHYSFS_ERRSTATETYPE__

{

void *tid;

PHYSFS_ErrorCode code;

struct __PHYSFS_ERRSTATETYPE__ *next;

} ErrState;

static ErrState *errorStates = NULL;

static void *errorLock = NULL; /* protects error message list. */

The API offers a way to get a description of the last error encountered on this thread. The canonical solution would have been the change the error reporting entirely, as keeping the last error code as internal state is considered bad form today (for good reasons), and instead ensure each API call would return an error code or exception when used. This would have, of course, required to change the whole API and all the callers.

Instead, I went for a quicker solution that made the last error code be a thread_local static variable inside PhysFS. This allowed me to get rid of most of the error code storage implementation, as there was no more need to handle a manually implemented linked list or lock anything. Unless the library is used in an environment where threads are really tight on thread local storage (which wasn’t my case), I found it to be a simple and elegant enough solution to the problem.

A lock might hide another

A surprise that came out of my new locking mechanism is that some lower bits of the library were not using any form of synchronization and simply relied on the main API lock to protect against data races. The archive file driver, for instance, shared a bunch of data meaning that two concurrent accesses to files in the same archive could result in a race condition.

Luckily, it turned out that access to those archive I/O handles were done a very few places so I could easily solve the issue by putting a lock at archive level. I would have searched for a more elegant solution if needed, but it turned that this one lock never showed up in the profiler, so I left it as is.

Still, that illustrated the fact that putting a global lock may lead to a bunch of unseen potential data races which will appear later once that lock is replaced by a more efficient mechanism, requiring changes in cascade throughout the implementation, down to the lowest levels.

The final lock I had to remove turned out to be on our side, as apparently someone had encountered an issue with PhysFS thread safety in the past on UNIX platforms and had added another spin lock on the call site of the API to address it. With the entire locking inside PhysFS now handled by std::recursive_mutex and std::atomic I could safely remove it.

Cascading bottlenecks

As my readers may know, removing a bottleneck somewhere does not always solve the issue. Quite often, it only makes the next one visible. In my case, the biggest one to show itself after I was done was PhysFS was our asset loading system. Since PhysFS used to perform so poorly, there was little point trying to load some assets in parallel, especially back when our main renderer was DirectX 9.

Graphics API were historically also bad at threading. For example DirectX 9 isn’t thread safe by default, and the “thread-safe” flag just enables a big mutex, exactly like PhysFS does. The official documentation recommends to not use it and instead do all API call on one thread. It’s one of the reason a lot of games still use a dedicated “rendering” thread to this date. While there are pros to this approach, the big drawback is that any model or texture loading as to be done in a serial fashion, which is quite sub optimal.

Fortunately more recent graphics API such as DirectX 11/12 and Vulkan are perfectly capable of loading textures, vertex buffers and the like in a threaded fashion. With the unexpected help of my great technical director, we were able to load most 3D models in parallel if the renderer supports it. This lead to another drastic improvement of loading times, as 8 cores can process vertices much faster than one.

One observation I’d like to highlight is that those upgrade requirements stack up. For example without those changes to PhysFS there would be little reason for us to port our older games to a newer version of DirectX unless was had plans to use the new graphics capabilities offered by the API. But with the file access contention issue solved, switching to a rendering API that supports threaded loading becomes much more interesting. Sometimes technical upgrades and refactoring are more valuable for the opportunities they open that for the immediate gains.

Tooling

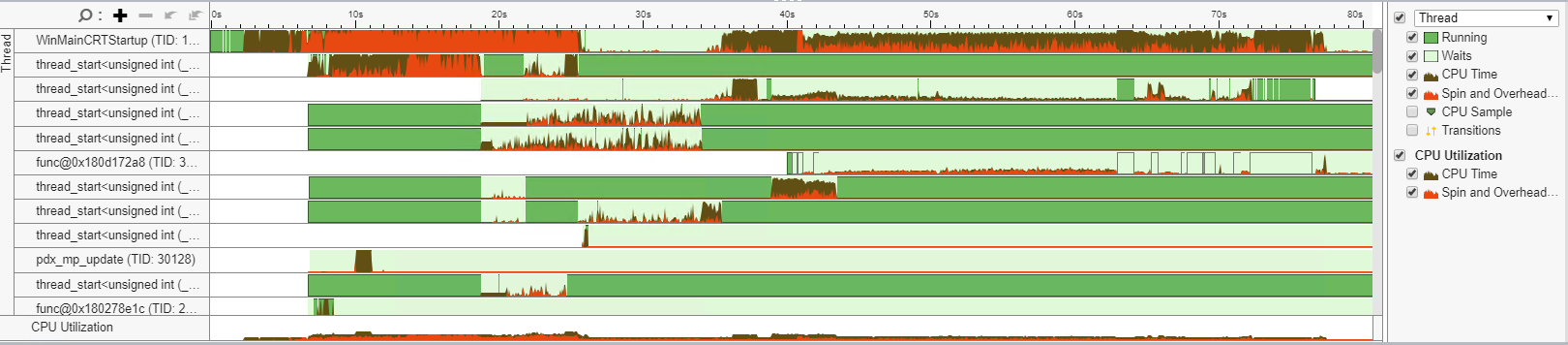

Before concluding this article, I want to stress out the importance of using a profiler to find bottlenecks. In my case this round of optimizations was strongly guided by Intel vTune.

The timeline visualization of cores activity in particular was quite handy to figure out when the CPU could be more effectively utilized. I found it useful to both verify assumptions but also to get a sense of some bits of the codeline that I wasn’t familiar with.

For example, it made me realize that all the game music in some of our titles was loaded upfront while the only one we really cared about during startup was the main theme. A moderate refactoring of the music player implementation allowed me to load only that particular track, and start a low priority background thread to load the rest for later once the player actually starts interacting with the ingame music player.

Knowing how your user will interact with your application is key when deciding when to do computation in the background, as it makes it easy to pick a time frame that is usually low on CPU utilization and won’t hurt performance of the main activity.

In Conclusion

First, see for yourself the difference on a side by side comparison I recorded on my home computer booting Stellaris (i7 2600k, 16GB of RAM, game installed on SSD drive):

Now, I do not consider myself new to threading and related topics, yet I still did not believe at first that I would be able to achieve such a drastic improvement. By the end of the iteration we had at least one game starting up more than twice as fast as it used to do on my machine (from over a minute to a few tens of seconds).

Looking back at my engineering school days in the 2000s and the years of work that followed, I now wonder how many opportunities were missed, both in teaching and applying those teachings. We keep saying over and over that modern CPUs are fast and can crunch an insane amount of instructions per second, but the true challenge is to make effective use of it. It is one thing to see the impact of threading or cache friendliness on slideware, but it’s another to apply it to a codebase that has existed for years or decades.

So, as many before me have recommended, please run your code through a profiling tool and see how good your CPU utilization is. It may come at the price of a costly refactoring, but the potential of getting twice or even ten times as fast is there…

… the only drawback is that now your composer needs to make the intro part of your game’s theme song much shorter.