What makes a game tick? Part 3 - Scripted Ticks

on C++, Game development

Scripting and editors are great for productivity. They allow designers and artists to work and iterate on gameplay and level design fast. They are also one of game programmers’ worst nightmare. And I’m not talking about implementing or maintaining them (not that it’s an easy job, more like it’s a different conversation). Today I want to talk about the impact on game performance that scripting languages and associated tools can have. And the more powerful they are, the worst it can get.

The last episode ended on a cliffhanger when we mentioned scripting in games. I had originally written some thoughts in the draft but I felt this would be better addressed in its own article to keep things concise and focused. So let’s talk about scripting!

Implementing gameplay

Scripting in older games was often fairly limited, more akin to an app configuration than anything else. From Doom to Half-Life the only thing you could script was a bunch of number like weapon damage and monsters hit points. For everything else you needed someone fluent enough in C or C++ to change game code.

Even for more recent titles from Valve, you can now have a peek at Team Fortress 2’s code and notice that just about anything about it is written in C++. Weapons, game modes, UI, Halloween event, you name it, it’s all done by programmers. There’s about 700 lines of C++ written just for the menu that allows the spy to pick a disguise with hardcoded path to assets and all.

If you’re used to making content with say, the Unreal Engine, this might sound like utter insanity. If you check out the source of the Lyra demo project for contrast, you will find that the behaviour of shooting the player’s gun is mostly (if not all) in blueprint, including the HUD reticle feedback, the firing animation, brass case ejection, muzzle flash, damage, bullet hole decal, you name it.

Valve has since moved to the Source 2 engine which might include scripting capabilities to avoid needing to write our own client and server DLLs to be implement gameplay, but without anything publicly available one can only speculate.

Either way, why does this concern us the performance minded programmer? Sure scripting sounds like it will save designers and artists a lot of time at the cost of writing and maintaining the tools they need, but that’s out of scope. For simulation/tick performance, does it even matter?

Here be dragons

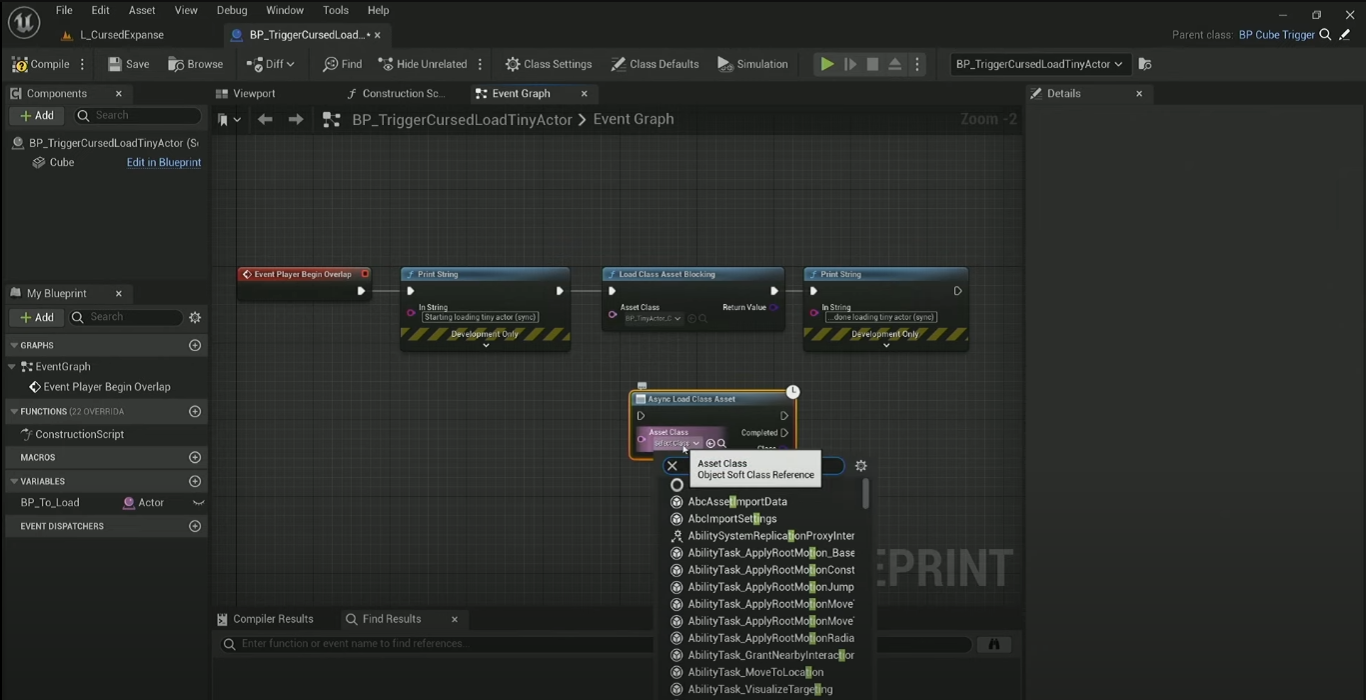

When I was first looking into Unreal Engine, I was suggested Ari Arnbjörnsson’s talk about performance and while it’s a good talk the content took me by surprise. For a talk about performance in AAA games, there was barely any actual code. In fact, the only C++ related issue in the whole talk was what I would consider a very weird usage of naked *new Object() that I would probably fail even a junior candidate for writing in an interview answer. Every other example issue was about an artist putting the wrong value in a blueprint, or a designer using the wrong function, triggering a synchronized asset loading when a player walks in a particular spot. And here start to see the problem: it took an artist or a designer to use the editor “wrong” but it required a (senior?) programmer to track it down and fix it.

It’s a tired quote by now, but as Uncle Ben said, “with great power comes great responsibility” and while I doubt he had game engines in mind his point still stands. The more powerful the scripting capability, the higher the ability to bring everything down to a crawl. And unlike a traditional performance hog caused by a programmer, the author of the issue and the one who fixes it may not be in the same discipline, or even in the same team.

This isn’t just to say “scripter bad, programmer good”. It goes both ways. The same way it may be hard for a designer or artists to expect a change they make to have significant performance impact, it’s hard for programmers to tell if firing a script event on every game object every Tick() is a problem or not. It all depends what the script can do and what it will do.

This comes with several issues. For starters, how hard is it from the programmer’s IDE to find and read a given script implementation. If the game is using Godot, the programmer needs to find the associated _process() for a given type in GDScript and read it. In the case of Unreal, they need to switch to the Editor, find the associated Blueprint and “read it”. Well visually parse it really, since Unreal scripting isn’t text based and while I know designers often like it, as a programmer if find it cumbersome to follow. With in-house engines (such as Clausewitz in PDS games) you would probably keep an instance of VS Code open on the game’s script folder and run a text search.

The obvious problem with this approach is that it’s not without friction. It would be good to be able to right click on a script call in the C++ code and navigate to it’s script counterpart. But that would require some sort of plugin able to quickly (and accurately) make the connection between arbitrary code and script, which while not impossible I haven’t seen done in practice. You may argue that Unity solves this by having its script language be C# which is basically the only language available (unless you pay for the C++ code and write native stuff), but I would counter that Unity does not have scripting because C# is way to complex and powerful to be considered a script language.

I understand that this last point may sound controversial, but to me the point of scripting is to provide a way for people who didn’t come from a software engineering background to implement some logic. I don’t think C# fits that definition. I’m willing to hear counter arguments but I would personally require a similar skillset between programmers and “scripters” on my team if they both used C#. I have had to work with designers who fancied themselves C++ programmers on the side without a tech background and while C# comes with less footguns I still wouldn’t trust it.

Unlimited power

The other big issue with scripting is the lack of guardrails. In my experience most script bindings do not offer a way to put boundaries on what a script can do or access. Often this is done by design to avoid needing to handle arguments and signature mismatch. Consider those three examples in an imaginary script language that looks suspiciously like Python:

def tick_v1(self):

# do some stuff...

def tick_v2(self, player, monsters):

# do the same stuff...

def tick_v3(mut self, const player, const monsters):

# also do the same stuff...

In the first version the only argument is the object itself. Assuming we want our ticking object to be able to access other objects, that means there’s probably some sort of singleton or global variables accessible to each tick() script function which allows them to query (and possibly mutate) the rest of the world. Or maybe they can walk some sort of object tree up and down until they find what they want through parents and children and siblings. The result is the same: they have access to everything that script can see.

In the second version we make data usage explicit, meaning the script promises it will only touch the object, the player and the monsters (and hopefully the language can enforce it with compile or runtime checks). The third version makes it even better because it explicits not only what will be accessed, but also if the data will be only read or also written to.

To the C++ programmer the 3rd example is probably the most natural. Especially if they have taken to heart the lesson that global variables are to be avoided. The trouble is, most (if not all) scripting systems I know of work like the first example. Any script call can possibly read and write to just about anything. If there’s one lesson to learn from functional programming it’s that pure functions with no side effect are the way to go for easier understanding.

This relates to performance because a lot comes down to constraints and promises. For example, think about map-type containers in C++. Only a few methods are allowed to invalidate iterators when called and they explicitly say so. Which means as long as we do not call them we can keep iterators/pointers to elements within it without the need to re-do the lookup. This property is transitive. As long as we do not pass a mutable reference to that map to a function, we can safely call a bunch of functions in our game and know our previously cached data is still valid.

Or, to think in game terms, suppose we ran some pathfinding between an AI NPC and the player and saved the result path. This is a fairly expensive operation and we would rather reuse the result if possible. As long as we do not call any Tick that will move the player, the NPC or obstacles along the way, this path is still valid and correct. But the instant we do, we have to recompute it. The issue becomes: firing a script event might touch nothing related to the path, but it might also teleport the player, or spawn an army of murderous enemies along the way and there’s no way to tell without reading the related script (which might be touched upon in the future by someone who had no way of knowing unless that is documented on both sides). The two obvious solutions are to either recompute the path each frame (which might negatively impact the game performance, especially if there’s multiple NPCs with this behaviour), or to assume the script event is safe (until it gets touched up and players start complaining the NPCs are “stupid” because sometime they run into hordes of monsters and die).

Restricted scripting?

As I mentioned a few paragraphs up, I don’t know of any scripting system that offers a way to restrict what a given script function will do through a mechanism of promises enforced either statically or dynamically. I don’t see why it couldn’t be done technically, but maybe designers would find it too annoying to use. Moreover, enforcing this would require to make the arguments part of the script function’s signature rather than just the name. This creates an obvious rendezvous problem where scripters would need to ask programmers to change the signature of events/callbacks and wait for those changes to be merged in their branch before they can do their work. And humans being humans, that means a reasonable chance that someone will decide they’d rather hack around the issue than write a JIRA ticket and wait for it to be done.

As a possible compromise, you could have the data usage declaration only on the script side (maybe restricted by object class?) and have the script invoke engine take advantage of it when possible (for example, if two script events don’t share data, they could be run in parallel in several threads). Again I do not know of any system that does, but we will come back to this idea but applied purely to gameplay code in a future episode.

Next time, we will continue with script, but will take a break from the architecture big picture talk and focus more on the script content itself and see a few examples of how it can have a funny impact on performance.