What makes a game tick? Part 7 - Data Driven Multi-Threading

on C++, Game development

During summer we explored some simple multi-threading models. They had the advantage of giving us a migration path for existing code that runs a very serial/imperative simulation. Now is the time to explore what other approaches we could take for a new project, or if we’re willing to refactor a lot of existing logic. Today we look at task-based parallelism.

Tasks-based programming

Using a series of connected tasks to achieve parallelism is a paradigm that has the advantage of being really easy to understand and illustrate. If you’ve ever looked at a project schedule diagram, you get the idea. Divide the work in a bunch of tasks and dependencies (eg: task A needs to be completed before task B can start). You’d likely need little work to integrate that form of execution in your game, most programming languages have solid libraries that handle executing a bunch of tasks on a given pool of work threads. They might even offer extras like priority scheduling (if both B and C can start and there’s only one thread available, prefer starting B over C or the opposite) and maybe preemption (if B is ongoing and C becomes available and is more critical, pause B and yield its execution thread to C instead).

While implementing a good task scheduler is quite a hard problem, there’s a lot of support libraries out there which makes it a somewhat easier problem in practice. The issue of using this approach for games lies elsewhere.

Game tick tasks?

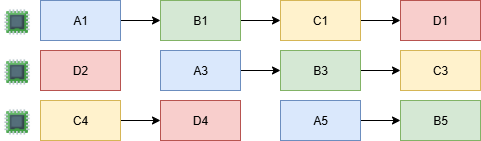

Task-based programming excels at scenario where tasks can own the data they work on, only sharing read-only state. Picture the data set as a unique_ptr that can only be owned by one task at a time, and moved between them as their execution flows. This is why you often see it used in networking and other I/O processing systems. Requests handled through some form of pipeline and parallelism achieved by handling multiple requests at the same time. Consider this example with a 4 step process:

In this case we have a simple pipeline A->B->C->D and 3 execution threads. To keep simple I kept requests on the same thread between steps, a thing that tasks schedulers may try to do anyway to keep the task data workset in their local core cache.

The problem for games is that our data model usually does not mirror that of a request processor. What works well to model a web server often breaks down for a game simulation.

As we’ve talked a lot before in this series, the problem is data sharing. For example, you could be tempted to adapt this model to a grand strategy game and say “a tick is the process of updating each country in the game through a series of tasks (simulate its economy, manage its troops, handle its diplomacy, etc..)” but you’d quickly run into the issue that none of these tasks can run in isolation for a given country, they all depend on the state of their neighbours, allies, rivals and other.

Alternatively we could try to define the tick as a series of systems to update (economy, construction, land warfare, navies, spies…) and hope that we have either enough systems or can subdivide their updates enough that we can have more that one task that can run at given point in time. This is essentially the route that Victoria 3 went for. And sadly it didn’t work. At all.

Task vs data dependencies

When the data is owned by the tasks in a task execution system, then the data dependencies are checked and enforced by the very fabric of the system. Task B cannot read or write data that Task A is currently processing because it has no way to accessing its variables. If Task C requires data from Task A and Task B, it can only run once both have finished and their data can be moved into Task C. The data flow and the execution flow are guaranteed to be in sync.

In the case of a game, where all variables are usually accessible (and accessed) through the World singleton, there’s no localized data flow that can be enforced. The programmer will write that Task C depends on Task A and Task B and the scheduler will know that it needs for A and B to be complete before C can start but that’s not enough for proper multi thread execution.

What if C also needs task D to be done but we forgot to declare it? What if A and B read and write to the same objects? What if we refactor C and it doesn’t need B anymore? Depending on which it is, the tick will at best suboptimal (C is waiting on a task it doesn’t need before starting) and at worst be prone to a bunch of data races.

On Victoria 3, the task system first implementation ran with only work one thread, and when it came time to use multiple ones it was found that the task graph was completely unreliable when it came to data races. The only way to tell if A and B could run at the same time was to look at the code they invoked to manually check for any possible data race, which was wildly impractical. Back to square one. (Before you source this post to say “PDS games don’t use threads”, I should add that individual tasks in Victoria can still use multiple threads by invoking parallel_for style loops, the game just won’t run 2 different tick tasks at the same time, unless it has been reworked since I left).

Data driven parallelism

As an alternative to logical task dependencies, what if we instead worked with physical (data) dependencies? If each tasks declares which objects/collections/systems it will read from and write to, we can establish a proper task graph that will ensure no data race can occur.

I’ve seen references to the idea all the way back to 2016 in Multithreading the Entire Destiny Engine and I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s even older (Kevlin if you read this, I’m sure you own a 50 years old book that mentions it). The concept of bringing this type of approach to GSGs was suggested by my good ex colleague Maciej who I still hope will make a talk about it one day.

For example, let’s get back to our 5 update tasks from last episode and let’s categorize what data they read and write to:

UpdateCountrieswill write to countries and read from provinces, as it will combine data from all provinces owned or controlled by the country.UpdateProvinceswill write to provinces and read from countries and armies to handle the fact that an uncontested army standing on a province should capture it for its owner.UpdateArmieswill write to armies and read values from countries and provinces for combat and pathfinding.UpdateNavieswill have a similar pattern but write to navies.- Finally,

UpdateAIwill read from just about everything and write down what the AI wants to do about it.

Put into a table, it would look like something like this:

| Task | Countries | Provinces | Armies | Navies | AI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UpdateCountries | 🖊️ | 📖 | |||

| UpdateProvinces | 📖 | 🖊️ | 📖 | ||

| UpdateArmies | 📖 | 📖 | 🖊️ | ||

| UpdateNavies | 📖 | 📖 | 🖊️ | ||

| UpdateAI | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 🖊️ |

From there, it’s easy to see which tasks can run concurrently without data races: two tasks conflict if they have either a read/write pair or a write/write pair for any given column. In this case it means the only tasks that are safe to run in parallel are UpdateArmies and UpdateNavies as their shared access pairs are either read/read or write/none.

This is obviously not great, but notice that the data granularity here is pretty big. Meaning if we could split some of those structures in two or more bits, maybe we would end up with more parallelism opportunities.

Let’s split the country object in 3: economy, diplomacy and modifiers (the Paradox name for collection of various bonuses and debuffs that applies to an object) and rebuild the table:

| Task | Economy | Diplomacy | Modifiers | Provinces | Armies | Navies | AI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UpdateCountries | 🖊️ | 🖊️ | 🖊️ | 📖 | |||

| UpdateProvinces | 📖 | 🖊️ | 📖 | ||||

| UpdateArmies | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 🖊️ | |||

| UpdateNavies | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 🖊️ | |||

| UpdateAI | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 🖊️ |

Still not great, we still have lots of conflicts. But now we can consider splitting the other problem dimension by subdividing the tasks. Say we divide the country update into several parts:

| Task | Economy | Diplomacy | Modifiers | Provinces | Armies | Navies | AI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UpdateModifiers | 🖊️ | ||||||

| UpdateProvinces | 📖 | 🖊️ | 📖 | ||||

| UpdateEconomy | 🖊️ | 📖 | |||||

| UpdateDiplomacy | 🖊️ | 📖 | |||||

| UpdateArmies | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 🖊️ | |||

| UpdateNavies | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 🖊️ | |||

| UpdateAI | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 📖 | 🖊️ |

Now we start to see some things emerge:

UpdateModifierscan run concurrent toUpdateProvincesUpdateEconomycan run concurrent toUpdateDiplomacy- As before

UpdateArmiesandUpdateNaviescan run concurrently

This approach allows us to refactor our Tick along 2 axis (data and algorithms) to improve concurrency. As a bonus, this should also improve maintainability as the individual tasks become smaller and easier to read, review and maintain. Finally, splitting data structures should also improve cache friendliness and increase performance (for more on that check out articles and talks about Data Driven Development, such as the one I gave at a few conferences).

Where’s the code?

Hopefully this pattern has picked your interest. But we have still some practical concerns to handle. For example, how do we declare a given tasks’ data accesses? Can we enforce them to make sure they don’t hide a sneaky data access that would break the whole thing? Is there support for this in commercial engines or can we reimplement it there for a reasonable cost?

Since this post is already getting big, we will have to focus on implementation concerns next time. See you there!